Five people living with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or in survivorship talk about their experiences with this serious and commonly misunderstood group of conditions.

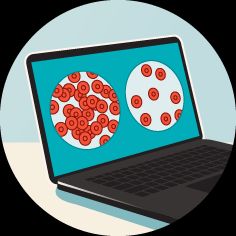

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of blood cancers in which immature cells in the bone marrow do not develop into healthy blood cells. When MDS were identified in the 1950s, they were called “pre-leukemic conditions.” In 1982, MDS was defined as a group of distinct disorders.

MDS often has no known cause. People who have

MDS is a rare diagnosis. According to the

What is known is that the experiences of people with MDS vary significantly. Some individuals are stable for many years with few symptoms. Some rapidly progress to life threatening complications. Some may experience anything on the large spectrum in between.

A stem cell transplant is the only potential cure for MDS, but most people are not medically eligible for this intervention. Treatments for MDS can

Healthline spoke with five people who are in MDS survivorship or currently living with an MDS diagnosis. They offer a glimpse into the diverse medical and personal experiences of people impacted by this group of conditions.

The following interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Richard Kimball: Prior to being diagnosed, I wondered why I seemed to be so susceptible to viral infections. Why am I sick? When I would crash my mountain bike, people would ask why I was bleeding like that. I also wondered, where did my wind and endurance go? So the diagnosis was in some ways a relief, because suddenly I could put the pieces together.

I read Suleika Jaouad’s book, Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted. Her diagnosis was MDS. In that book, she had Susan Sontag’s quote, “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.”

I think this is a [lesson] that I wish I had more squared away in my head. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later, each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place. I just thought I would always have the “good” passport.

Jeff Soucy: I had absolutely no symptoms. So the diagnosis came as a surprise. I knew nothing about MDS before. For me, blood cancer was only leukemia. So, actually, the diagnosis wasn’t clear. At first, I thought that I was in a pre-cancer place.

It was actually not said to me with the words, you have cancer. So it took me coming back home and looking it up online to figure out that it was cancer. It’s not so much what I wish I knew before but what I wish was better explained to me.

I’m a strong advocate now for regular blood work because that is why we caught it as early as we did.

Jill Dolgin: As a healthcare professional and professional patient advocate, I knew that when I was treated for breast cancer 30-plus years ago that chemotherapy could potentially cause MDS. Rare, but it could happen. And knowing that information would not and did not change how I managed the immediate issues of breast cancer.

Maybe I would’ve done more research before I went into my bone marrow biopsy to fully understand what MDS is. But I didn’t want to jump ahead. I’ve had this chronic

Ross Bagully: I didn’t know when I was diagnosed that there’s a wealth of information available. I don’t know why anybody once diagnosed wouldn’t take advantage of all the information that is out there and all the support from the MDS Foundation, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), and Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation (AAMDSIF).

Those three organizations are fabulous and have so much information and people on their staff who want to be helpful and who are always available to talk with you. It’s people who really provide hands-on help whenever they can, whether it’s finding a clinical trial or making sure you have the right medical team that you’re working with.

Junia Papas: To live my life to the very fullest. I just never thought of myself as the type that would get a diagnosis like this, which I’m sure no one else does either. You think you’re going through life and everything is going to go on the trajectory that you’re thinking.

But I mean, it happens. It happens to people much younger than my age. And I think what I wish I would’ve known before is that I should have lived my life even more to the extent that I could, to the very fullest. Also probably to be kinder to myself even before then.

I’ve always been very empathetic to people who have illnesses, even illnesses that you can’t see. So I don’t think I would’ve changed that part at all. But now I am one of those people. So it feels very different.

KimballI think the prognosis is very hard to understand. The science is hard to understand. We all ask the doctors, “Where’s this going to go? What’s going to happen?” They answer it [by explaining], when I started, what’s called the IPSS-R rating.

Based on where you were on that continuum, you had some sense of what your life span was likely to be. My doctor was great about explaining not to over extrapolate from that. But I think the diagnostic parts of this are very challenging. Science is out there really fighting for us, but [it] can’t give us all the answers.

“When I do tell people that I do have a form of blood cancer, a lot of times, people just expect that I should be in some sort of treatment. And when I tell them I’m on watch and wait, they think I’m doing something wrong. They think you should be getting a second opinion, that your doctor isn’t treating you correctly.” — Junia Papas

Soucy: I’m lucky today to be living free of it, cured. I think for anyone who is either cured or in remission, I think my biggest battle — the hill I will die on — is advocacy for mental health.

I had a stem cell transplant. Everything went very well. And I had pretty much only good news to share all the time on my social media and with my family and friends. And it gave the sense that I was OK. But even though my body was getting better, my mental health experienced a lot of dissonance.

I had new limitations, different stamina and abilities that were not quite the same as before. And just my immune system that was weak and having to live life quite differently and consider a lot of different things. As I live my life and as I try to go back to some sense of normalcy, that will never be the same as the normal that was before.

What I wish people would know is that it’s a lifelong trauma. Just because someone is well physically, it doesn’t mean that they’ll ever be fully healed mentally and emotionally.

It’s very odd to get a blood cancer diagnosis because it is not something that is tangible, as opposed to a tumor that is visible on a scan. So it’s much harder to wrap your head around being sick.

Dolgin: It’s such a heterogeneous disease that it affects people differently depending on which cell line is affected. People will say, oh, you look so good. You don’t look like you’re sick. But I think it’s [about] understanding that I’m tired. And it’s just [about] helping people understand that you may not be able to do the things that you did before.

I’m considered low risk, but I think the challenge with low risk is that we’re called “watch and wait.” They just keep doing complete blood counts (CBCs) every 3 months. And I really think it’s the “watch and worry.” It really makes you evaluate or reevaluate, if this does progress, what am I going to do about it?

After 37 years, I don’t really think about breast cancer, and now I’ve got something else to worry about. On the other side of it, that watch and worry for me is a reminder that life is short. The fact that I’m still here 37 years after my breast cancer diagnosis is because I’ve been so proactive.

Bagully: One of the challenges is that MDS is so different for different people. And I’m not even talking about the collection of potential diseases that are categorized as MDS, but rather the individual experiences vary so dramatically.

An awful lot of people with MDS I know suffer from being just exhausted all the time. That’s a very, very restrictive result of the disease. I’ve been the opposite extreme. So I’ve been very, very fortunate.

Papas: Even though I look fine, I’m really, really tired, just very exhausted. And so when people look at me using a wheelchair at the airport and maybe not volunteering for certain activities in communities or not working, they might look at me like, oh, you are fine. And the judgment that comes with it I think is very difficult for me.

I wish people knew what MDS is.

When I do tell people that I do have a form of blood cancer, a lot of times, people just expect that I should be in some sort of treatment. And when I tell them I’m on watch and wait, they think I’m doing something wrong. They think you should be getting a second opinion, that your doctor isn’t treating you correctly.

And so I wish people would understand that there are many, many forms of blood cancer, and you attack all of them in a different way.

Kimball: The only cure right now is a blood stem cell transplant from a matching donor. And doctors are looking for people with genetic markers and that closely align. Registering for the National Marrow Donor Program is so simple.

Soucy: Number one, become a donor. That’s the biggest gift I felt that I could receive — when someone told me they went to register. I was one of the incredibly lucky ones to have four 100% matches in the registry, which is very rare when so many people are struggling to find even one [match].

Also, don’t tell people, “I’m here for you if you need anything.” Ask us what we need. Most people are very uncomfortable asking for help, and so being active in your support versus asking us to make the effort to go towards you makes a difference.

Also, do we talk about cancer or not? I think there is space for everything. Don’t assume that because someone was diagnosed with cancer that your entire relationship needs to revolve around that.

I have a friend who just showed up at the hospital with chips and sodas out of nowhere unprompted, and it was just so lovely. Regardless of your comfort level with cancer, it shouldn’t affect the nature of your friendship or your relationship with the person.

Dolgin: They can be of assistance by researching reliable resources to help manage the disease: treatment options, access to treatments, cost of care, Centers of Excellence, and specialists. Not all oncologists or even hematologists know how to manage this disease.

Six months before I was diagnosed, I got a text message from a good friend of mine. She started to tell me that she had these bruises and they think she has MDS. She went from MDS to leukemia within 2 weeks.

When I was faced with that information from her, my immediate response was to start flooding her with information about resources. And her response to me was, if it’s anything about my prognosis or treatment, I don’t want to know right now.

So it dawned on me that I needed to meet her where she was at. I was flooding her with too much information at a time when she was still dealing with this diagnosis.

It’s helpful for friends and family to understand what’s out there. But it’s also about understanding where people with MDS are in their journey.

Bagully: I think there is a tendency for people who are not directly involved not to recognize how significant MDS can be. My initial doctor didn’t even identify it as a blood cancer, which obviously it is.

So I think there is a tendency for people to be dismissive of it and not recognize how dangerous and how serious a disease it is. That would include a lot of hematologists who don’t deal with it very often and don’t have that depth of knowledge.

I think a broader knowledge on most people’s parts, including in the medical profession, would be very good.

Papas: To be more compassionate with us. I have anemia. So my brain function is not the same as it was. I’m a PhD and I’m a certified archivist, so I’m an extremely learned person, but I can’t remember things. I make mistakes, really little dumb mistakes that normally I wouldn’t. And it’s because I am so very tired.

So I think understanding that it’s not really who I am — it’s the illness that makes me not be able to remember names or all sorts of different things.

“I was a people pleaser, and I’m very independent. I’m that type of person who does not want to ask for help. So there have definitely been friends who have figuratively sat me down to say, ‘Jeff, ask us. People want to help you. Let us help you.'” — Jeff Soucy

Kimball: By far my wife, my sweet wife, Mary Lou. And my sisters, and my good friends. Also, valuable resources like the MDS Foundation. They’re constantly helping me in various ways.

Also, healthcare professionals. Just in the last year, I’ve given blood 62 times. That means somebody is checking you in, somebody’s drawing your blood. They’re always somewhat anonymous, but they’re just amazingly kind people.

Soucy: I was a people pleaser, and I’m very independent. I’m that type of person who does not want to ask for help. So there have definitely been friends who have figuratively sat me down to say, “Jeff, ask us. People want to help you. Let us help you.” So I think that the advocacy was for me, against me, against my own instincts.

It was people putting me in front of my own instincts and being like, “Hey, you need to let go of some control and let people help you because they want to help you.”

And for people to tell me, you can rest. My doctors, especially, drilling into my head that when I’m resting, my body’s working really hard. It’s not wasted time. Because that has never been my understanding of rest.

Dolgin: I think my biggest advocates are those individuals who I have met and worked with over the years of me working in this profession [Note: Jill Dolgin is a clinical pharmacist and patient advocate.] One of my first phone calls was to oncology nurses and social workers to say, “What do I do with this?”

My friend immediately connected me with Tracey at MDS. I had been on the MDS Foundation website, but to sit down and talk with Tracey as Executive Director of the organization, for me was very helpful.

Bagully: Of course, my family. But I believe my biggest advocate and the person responsible for my health and welfare is me. Believe me, I love my doctor. But my health is my responsibility.

Anyone, especially with a serious disease, if you don’t take care of yourself, take responsibility for yourself, make sure you are getting what you need and learn everything you can about what you’re dealing with — then that’s just foolish. I can’t comprehend why anybody would abrogate that responsibility to someone else.

Papas: That would be my husband. He is an amazing advocate for me. He’s just been really helpful because a lot of times I will be too tired and I cannot stick up for myself, for instance, because I can’t think straight. And then he will absolutely help me and take up for me and I’m really grateful for that.

Also, I’m very grateful for the professional advocates like the MDS Foundation. They’ve just done so much to make the diagnosis of MDS something that the community and the medical community is aware of.

Kimball: I find solace in the natural world. I tend my forest, almost like a forester, and go for walks with my wife every day. I have a friend who says, “When I’m skiing, I don’t have cancer.” And I think he’s right.

Every single day I’m studying the latest MDS research, I’m following clinical trials, I’m learning. I try to study and learn so that even though I don’t have full agency to the extent that I can claim agency, I want to be fully on board.

Soucy: Setting boundaries is part of self-care. Also, I’m trying to shift my perspective on physical activity. I’m trying to understand that all of these things are for my mental well-being just as much as my physical well-being.

Being 9 months off work and spending a lot of that in bed, it was crazy to see how my body was not able to do the simplest things. So you realize the importance of physical activity. Yoga and Pilates are two things that I like to experiment with, very gentle and efficient.

I used to be a performer, and I’ve been a stage manager since 2019. Coming back has rekindled my interest in more creative work or more creative expression.

And therapy. One of the big takeaways from therapy was that even with healthy coping mechanisms, I still went through trauma, and I still need to deal with that at some point.

So, understanding that I’m not alone in this very lonely journey.

Dolgin: I think for me, self-care is really understanding and being patient with my limitations, physical and psychosocial. I think it’s taking a nap when I need to. It’s getting out and exercising when I need to. It’s doing nothing if I need to. I think it’s just recognizing that I need to be more patient with myself instead of pushing myself.

Bagully: My wife and I walk 7 days a week, depending on the weather. We do extended distances, 5, 7, 8 miles a day, that certainly helps. I eat a reasonably good diet in general. A lot of fruits and vegetables; we don’t eat a lot of red meat. We eat fish, we eat chicken, and we eat turkey.

Papas: I try to spend as much time in nature as I possibly can. Even just a stroll in the forest. If I don’t have energy for that, I just sit in my backyard and just really enjoy the foliage and the sky. Just to sit quietly in nature really does help me very much for self care.

Kimball: I created this process, I call it Farther On, and I put a group of people together. We journal a question every month.

MDS was a kind of an alarm bell. I try to make sense of a part of life, remembering all the good things, thinking, just articulating and kind of in a journaling way, trying to capture it. It’s therapeutic.

Soucy: Donate blood. Don’t just become a donor for bone marrow, but go donate blood if you can.

Dolgin: I think, for people with MDS, it’s just making sure you’re communicating with your family and friends as much as you want to share with them. But I think it helps, I think, to have them involved because if you do progress, they can be in a position to help and understand what you’re going through.

Bagully: Obviously, when someone gets a diagnosis like this, it’s scary. Sometimes, the more you learn, it scares you more. But then you also see a path forward. I am still totally treatment-free after 10 years and living a very good, active life.

So people shouldn’t panic and lose hope. Rather, they should accept that this is an opportunity for them to take control of their health and do everything they can to make it better and to work through this process.

Papas: To know we’re not alone and there’s always hope. I’ve been in this for 4 years, and many people have been in it a whole lot longer than I have, and they’ve had much harder experiences than I have.

But I feel like with all of us banding together, something will happen, a solution will be found. The more and more we get it out there, the better it will be for all of us.