Living with the rare condition of IgA nephropathy can feel lonely. Patient advocate Stuart Miller shares his treatment journey and how to stay connected with those who understand.

Although there’s currently no cure for IgA nephropathy, treatment options have improved in recent years. Multiple medications are now available to help limit inflammation and kidney damage, which may help prevent or delay kidney failure.

Attending regular checkups with a nephrologist, eating a kidney-friendly diet, and taking steps to cope with stress and anxiety are also important for managing this condition.

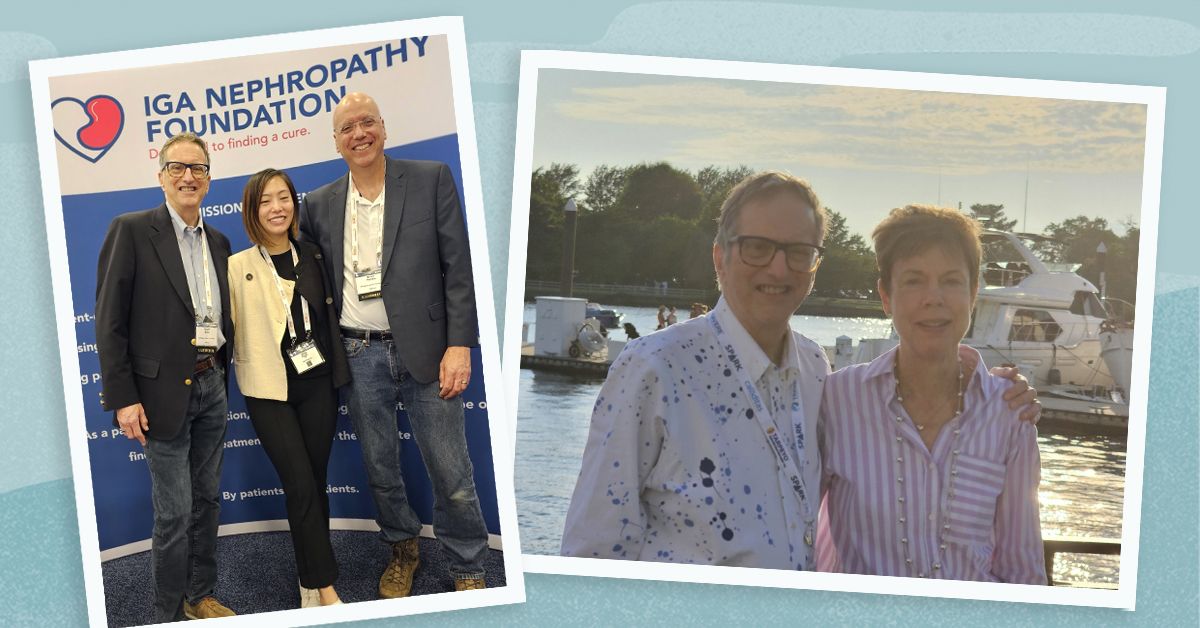

We spoke with Stuart Miller, director of strategic relationships at the IgA Nephropathy Foundation, to learn about some of the challenges people with this condition may face and strategies for managing those challenges.

Read on to learn more about his experience and tips.

Miller learned that he had IgA nephropathy in 2008 when he was in his mid-50s.

Routine medical tests had shown for years that he had small amounts of protein in his urine, but his doctors hadn’t been concerned. Then, he started to see a new doctor who suggested it might be a sign of something serious.

“I moved to the Atlanta area and saw a new primary care physician, and the first physical we did, he said, ‘I don’t care what anybody else has told you, you need to go see a nephrologist as fast as you can because your kidneys aren’t working the way they should be,’” Miller told Healthline.

He was referred to a nephrologist, who tested his glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which measures how well the kidneys filter blood. His GFR was 54, well below the typical level of 90-plus.

“They gave me the option to either go about my life and see what happens or get a kidney biopsy to learn exactly what the problem was. The way they explained the biopsy process, it was kind of risky, so I said I would just continue the way things were,” said Miller. “Then, about a year later, my kidney function had continued to decrease, and they said, ‘You need to have the biopsy.’”

The biopsy showed that Miller had IgA nephropathy, which was difficult news to receive.

“It changed my life quite a bit, as you can imagine, getting a diagnosis for a rare disease that there’s no cure for. It was sobering and very scary,” he said.

IgA nephropathy is a chronic condition that may get more severe over time. It can potentially lead to kidney failure, which requires dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Miller struggled with the knowledge that his condition could get worse.

“Mental wellness is often a challenge for people living with IgA nephropathy because you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen, whether your kidney is going to work or fail. I worried about that a lot,” he said.

He had some friends and family he could talk with, but the invisible nature of IgA nephropathy can make it harder for people to understand the challenges it poses.

“Due to the nature of IgA, we don’t really look sick — even though the labs and doctors would say differently. So, I didn’t get much sympathy from a lot of friends and family because they didn’t really think that I was sick,” Miller said. “One of the biggest challenges was finding the right people to talk with, who were willing to support and listen to me,” he said.

After getting his diagnosis, Miller attended regular checkups with his nephrologist and got regular lab tests to monitor his kidney function and check for signs of kidney failure.

“I worried about not knowing what the next lab test was going to show,” he said. “And in my case, it took about a year before they knew that my kidney was going to fail. It was just a question of when. So, I knew the worst was coming, but I couldn’t do much about it.”

Multiple medications are now available to treat IgA nephropathy, including budesonide (Tarpeyo), sparsentan (Filspari), and iptacopan (Fabhalta). But Miller’s treatment options were more limited when he learned he had the condition.

His nephrologist encouraged him to take fish oil supplements and prescribed prednisone, a steroid that suppresses the immune system. It helps reduce inflammation but can also cause side effects, such as irritability, agitation, and increased risk of infections.

“I was able to stay on the prednisone, but not without side effects. And it did help maintain my kidney function for a while. But at some point, it stopped working, and my kidneys started to fail,” Miller said.

Along with taking medication, he adjusted his diet to reduce sodium and protein intake. Eating too much sodium causes your body to hold onto water, which increases blood pressure in your kidneys. Consuming too much protein makes your kidneys work harder. Eventually, Stuart switched to a primarily plant-based diet. Although more studies are needed, some research shows that limiting or avoiding animal protein may help limit kidney damage and delay kidney failure in people with chronic kidney disease.

By 2018, Miller’s lab tests showed that his kidneys were close to failing.

People with kidney failure often get dialysis while they’re waiting for a kidney transplant or if a kidney transplant isn’t a treatment option for them. Dialysis is a procedure that helps remove waste and excess fluid from your blood. Typically, it takes a few hours every few days, and a person can experience fatigue afterward. Dialysis can be expensive, time consuming, and disruptive to daily life. However, it’s potentially lifesaving if you have kidney failure.

Miller’s wife decided to donate one of her kidneys so he could avoid dialysis and get a kidney transplant before his kidney function got worse. “I’m very lucky she’s willing to make that sacrifice and take that risk,” Miller said.

Blood type, tissue type, and other factors affect how compatible an organ donor is with an organ recipient. His wife’s kidney wasn’t the right match for him, so they took part in a paired kidney donor exchange. She donated her kidney to a woman in California, and that woman’s mother donated her kidney to Miller.

In the weeks after his transplant, Miller’s body showed signs of rejecting the donated kidney. His healthcare team was able to adjust his medication and get him back on the road to recovery.

“I probably won’t get a second transplant because of my age, so that’s always in the back of my mind, but you do the best you can to deal with it and try not to let it affect your everyday life,“ Miller said. “I’m lucky. I’m able to live my life and have never had to go on dialysis.“

It’s important to understand that a kidney transplant may not necessarily be a cure. In some cases, the other kidney could become damaged or stop functioning. The transplanted kidney could also be affected by IgA nephropathy. The kidney recipient must discuss ongoing treatment with their nephrologist, such as taking one of the new medications for IgA nephropathy.

For over a decade, Miller managed the ups and downs of IgA nephropathy without meeting anyone else who was living with the condition.

That changed in 2019 when he attended an externally-led patient-focused development meeting hosted by the

“I went there, and all of a sudden, I saw 160 people that were going through the same thing. I was listening to their stories and hearing people say they’d experienced the same things. I realized, ‘Wow. I wasn’t imagining this,’“ he recalled. “You can talk to all your friends, you can talk to all your family, but only when you talk to someone else who’s going through the same journey that you’re going through does it really make a difference,“ he said.

Miller was already volunteering as a patient advocate with the NKF and eagerly approached the IgA Nephropathy Foundation to learn how he could get involved with them.

Miller encourages people with IgA nephropathy to learn about the condition and treatment options and take steps to support their kidney health proactively.

“If you get diagnosed with IgA, make some changes. Be your best advocate, learn about the disease, ask your doctor questions when you go on your visits and get your labs, and try to find ways to manage that mental stress that comes with knowing you have this,“ he said.

He also encourages others to reach out to the IgA Nephropathy Foundation for support and to connect with people living with the condition.

“The biggest resource that the foundation provides really is a sense of community — a community where people can go and talk and meet with other patients who are going through the same experience,” he said. “It also has great tools and resources for understanding your labs and treatments and so forth.”

“There’s no cure yet, but if you can make your kidneys last longer, that’s a big positive,” he said. “There are three new treatment options, there’s probably more coming to market soon, and there’s a bunch of clinical trials, so there are a lot of treatment opportunities. There’s hope!”

Stuart Miller has been living with a diagnosis of IgA nephropathy since 2008. He works as the Director for Strategic Partnerships at the IgA Nephropathy Foundation and volunteers as an advocate for the National Kidney Foundation and an ambassador for the American Association of Kidney Patients. In these roles, he helps spread the word about organ donation, encourages patients to become their own advocates, and helps work on legislation to improve the lives of people with kidney disease.